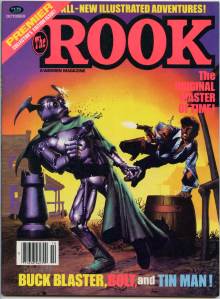

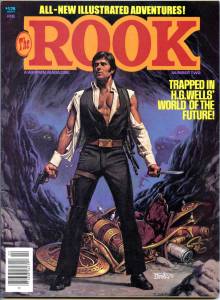

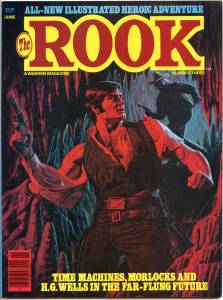

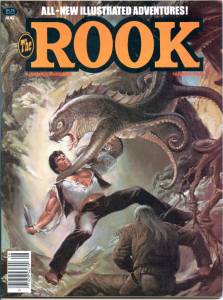

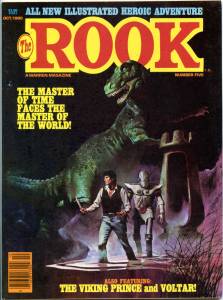

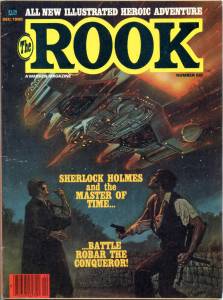

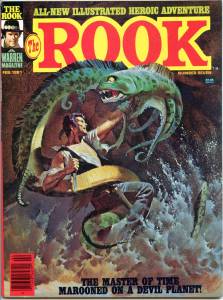

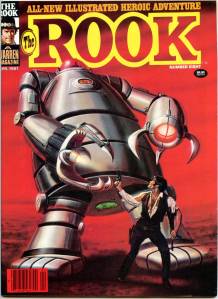

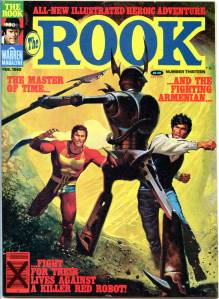

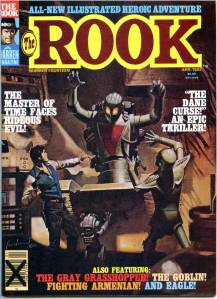

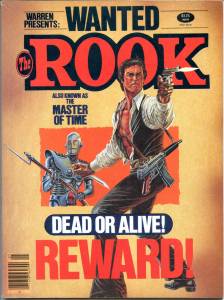

The Rook is a fictional, time-traveling comic book adventure hero. He first appeared in March 1977 in American company Warren Publishing‘s Eerie, Vampirella & Warren Presents magazines. In the 1980s, the Rook became popular and gained his own comic magazine title of the same name, The Rook Magazine.

Category: Independent Bronze Age

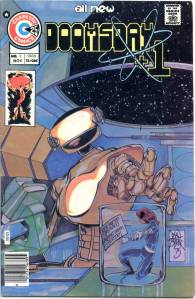

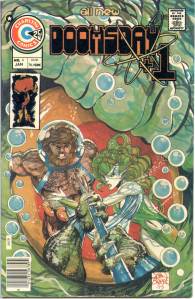

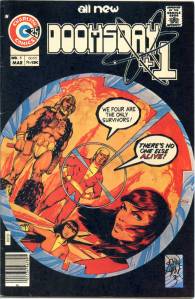

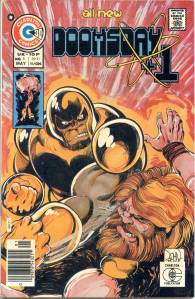

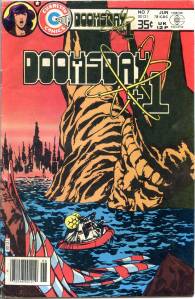

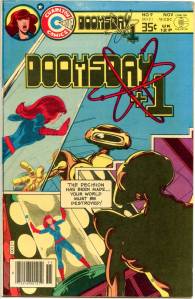

Doomsday +1 (1975)

The series takes place in a near future in which a South American despot named Rykos launches his sole two atomic missiles on New York City in the U.S. and Moscow in the U.S.S.R. The two superpowers, each believing the other has launched a first strike, retaliate. By the time American president Cole and a Russian premier with the first name Mikhail have realized their errors, their fully automated nuclear-missile systems can not be countermanded.

Only hours before the apocalypse begins, a Saturn VI rocket launches bearing three astronauts: Captain Boyd Ellis, United States Air Force; his fiancée, Jill Malden; and Japanese physicist Ikei Yashida. Weeks later, after the post-apocalyptic radiation has subsided to safe levels, their space capsule lands upon a melting Greenland ice field, where the three ally themselves with Kuno, a 3rd-century Goth revived from his ice-encased suspended animation.

The four encounter a Russian scientist/cyborg in Canada, where they commandeer a futuristic jet plane; undersea dwellers; and brutish U.S. military survivors, among others.

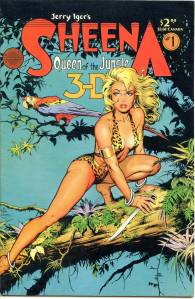

Sheena 3-D Special (1985)

The first issue of Blackthorne’s long-running 3-D series, featuring Jerry Igers classic jungle princess, hero of pulps, comics, and the big and small screens. Absent from comics for almost three decades, this presents some of her 1950s adventures in 3-D format, including one by legendary good-girl artist Matt Baker. But the main draw for many fans will be the stunning cover by beloved artist (and Rocketeer creator) Dave Stevens. Also featuring an introduction by creator Jerry Iger, a Snarzan the Ape spoof from Great Comics (1941) #1, and a Congo King story with art by legendary good-girl artist Matt Baker. Heroine in the Jungle; Sargasso of Lost Safaris; Snarzan the Ape in Mein Kemp Von Der Chungle; Congo King; Spoor of the Dancing Skeletons. 32 pages, B&W with 3-D effects.

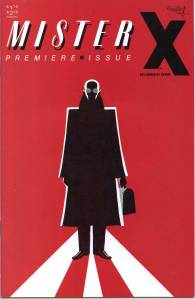

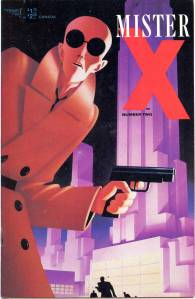

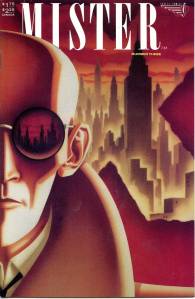

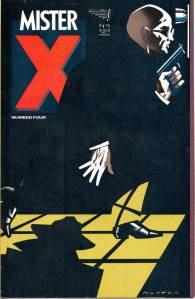

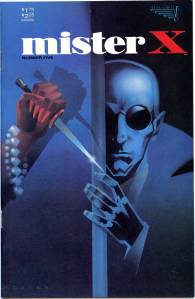

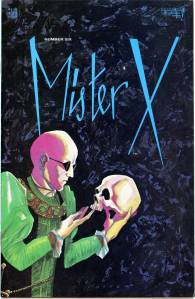

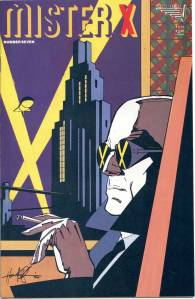

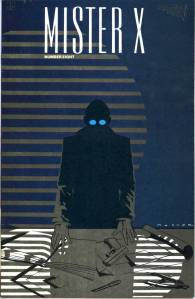

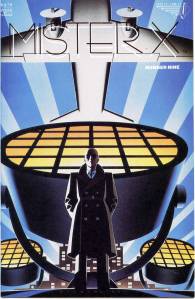

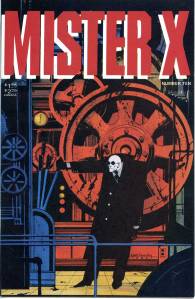

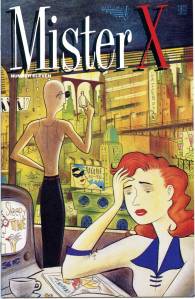

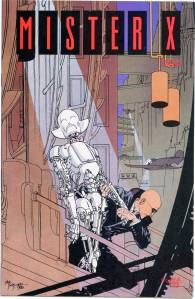

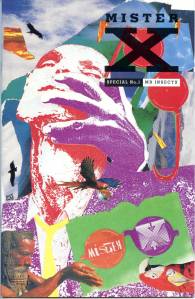

Mister X (1980’s)

Created by album and book cover designer Dean Motter, Mister X was developed for a year in close collaboration with comic artist and illustrator Paul Rivoche, whose series of poster illustrations stirred up great interest in the project. The series published early work by comic artists who would later emerge as important alternative cartoonists, including Jaime Hernandez, Gilbert Hernandez, Mario Hernandez, Seth, Shane Oakley and D’Israeli.

A highly successful promotional campaign with posters and ads followed for the next year, while Motter and Rivoche struggled to produce an actual issue of Mister X. When Rivoche quit, Vortex Comics president Bill Marks became more skeptical than ever that Motter would be able to produce the series on time, and decided to turn the work over to the Hernandez brothers. The first four issues were written and illustrated by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, with additional writing by Mario Hernandez. The Hernandez brothers quit over payment delays from Vortex. Issues 5 through 14 of the series were then written by Motter, with issues 6 through 13 illustrated by Seth.

Mister X’s influence can be seen and was acknowledged in films like Terry Gilliam‘s Brazil, Tim Burton‘s Batman, and Alex Proyas‘ Dark City.

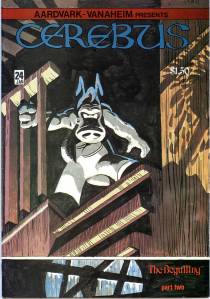

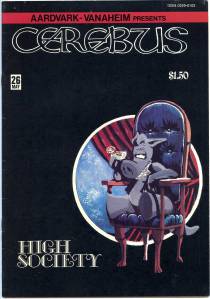

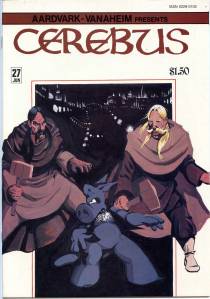

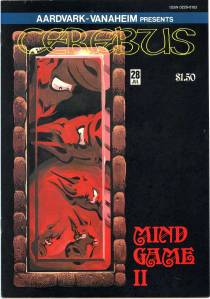

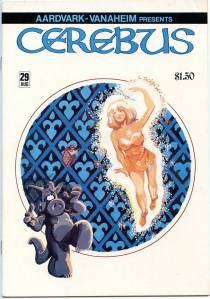

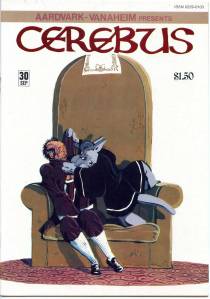

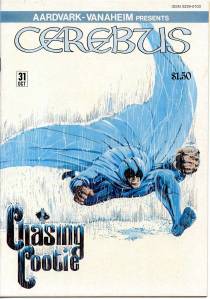

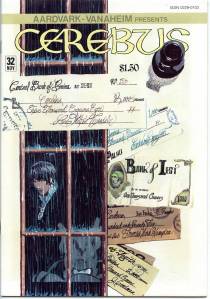

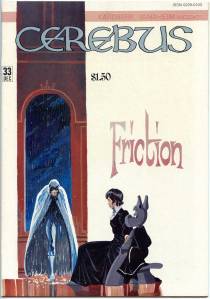

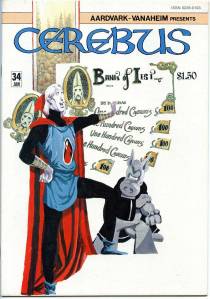

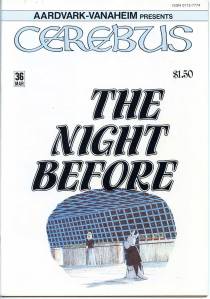

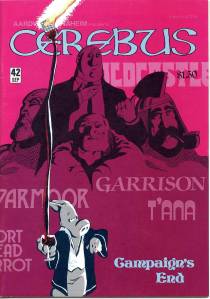

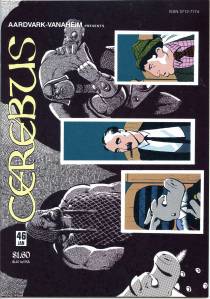

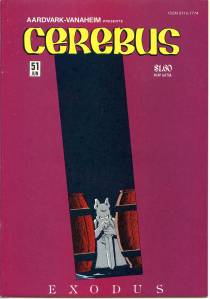

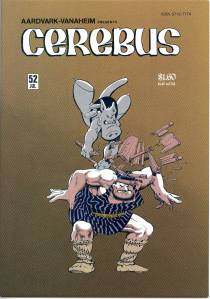

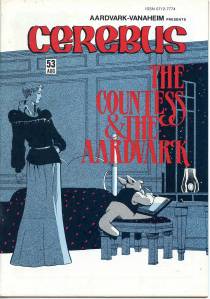

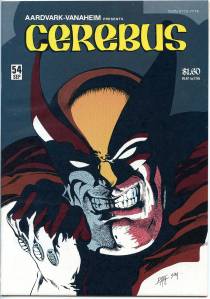

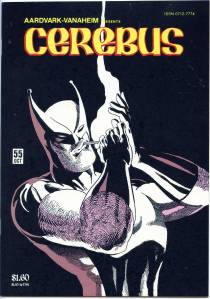

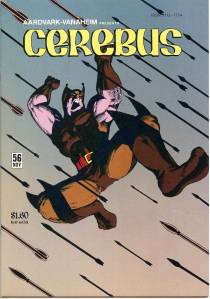

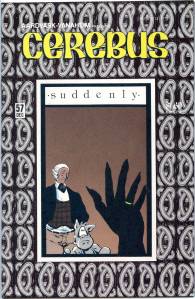

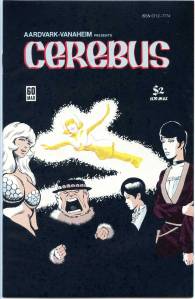

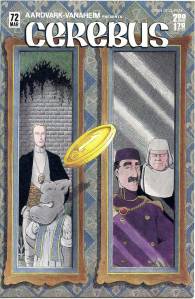

Cerebus (1977)

Cerebus the Aardvark is a series created by Canadian cartoonist Dave Sim, which ran from December 1977 until March 2004. The title character of the 300-issue series was an anthropomorphic aardvark who takes on a number of roles throughout the series—barbarian, prime minister and Pope among them. The series stands out for its experimentation in form and content, and for the dexterity of its artwork, especially after background artist Gerhard joined in with the 65th issue. As the series progressed, it increasingly became a platform for Sim’s controversial beliefs.

The 6000-page story is a challenge to summarize. Beginning as a parody of sword and sorcery comics, it moved into seemingly any topic Sim wished to explore — power and politics, religion and spirituality, gender issues, and more. It progressively became more serious and ambitious than its parodic roots — what has come to be dubbed “Cerebus Syndrome“. Sim announced early on that the series would end with the death of the title character. The story has a large cast of characters, many of which began as parodies of characters from comic books and popular culture.

Starting with the High Society storyline, the series became divided into self-contained “novels”, which form parts of the overall story. The ten “novels” of the series have been collected in 16 books, known as “Cerebus phonebooks” for their resemblance to telephone directories. At a time when the series was about 70% completed, celebrated comic book writer Alan Moore wrote, “Cerebus, as if I need to say so, is still to comic books what Hydrogen is to the Periodic Table.”

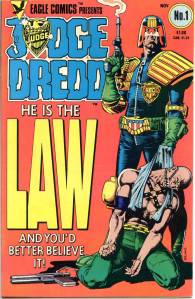

Judge Dredd – Eagle Comics (1983)

Judge Dredd is a fictional character who appears in British comic books published by Rebellion Developments, as well as in a number of movie and video game adaptations. He was created by writer John Wagner and artist Carlos Ezquerra, and first appeared in the second issue of 2000 AD (1977), a weekly science-fiction anthology. He is that magazine’s longest-running character.

Joseph Dredd is an American law enforcement officer in the dystopian future city of Mega-City One. He is a “street judge“, empowered to summarily arrest, convict, sentence, and execute criminals. Dredd’s entire face is never shown in the strip. This began as an unofficial guideline, but soon became a rule. As John Wagner explained: “It sums up the facelessness of justice − justice has no soul. So it isn’t necessary for readers to see Dredd’s face, and I don’t want you to”. Time passes in the Judge Dredd strip in real time, so as a year passes in life, a year passes in the comic. The first Dredd story, published in 1977, was set in 2099, whilst stories published in 2015 are set in 2137. Consequently, as former editor Alan McKenzie explains, “every year that goes by Dredd gets a year older – unlike Spider-Man, who has been a university student for the past twenty-five years!”. Therefore Dredd is over seventy years old, with over fifty years of active service (2079–2136), and for some time characters in the comic have been mentioning that Dredd is not as young and fit as formerly.

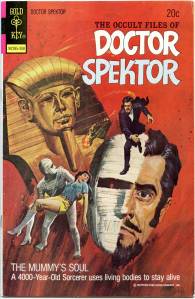

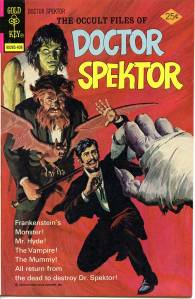

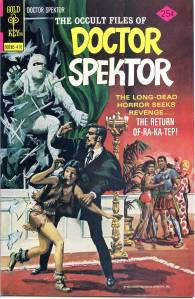

The Occult Files of Doctor Spektor (1970’s)

After his first appearance in a 10-page story in Mystery Comics Digest #5, Dr. Spektor was spun off into his own title, The Occult Files of Doctor Spektor. The series ran for 24 issues (May 1973 – February 1977). His final original story appeared in one issue of Gold Key Spotlight (#8, August 1977). Jesse Santos replaced Spiegle as artist on the series, and remained there for the entire run.

Dr. Spektor appeared in all four issues of Gold Key’s Spine-Tingling Tales (1975–76), where he provided linking narration for some of the stories within. (These stories were reprints from Mystery Comics Digest that dealt with characters who later appeared in his title). He also had stories he narrated in Mystery Comics Digest #10, #11, #12, and #21, and articles in Golden Comics Digest #25, #26, and #33.

Under the Whitman Comics name, issue #25 was released in May 1982. It reprinted issue #1, but with a line-art cover instead of the original painted cover.

In 2014, Dynamite Entertainment released a new version of “Doctor Spektor”, written by Mark Waid and drawn by Greg Pak, as part of the company’s revival of several Gold Key characters (which also included Magnus, Robot Fighter, Dr. Solar and Turok)

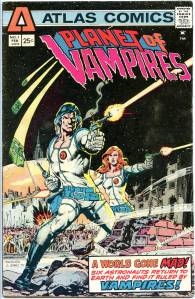

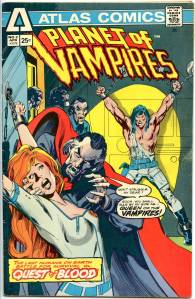

Planet of the Vampires (1975)

In the far-off era of 2010 AD, astronauts return from space to find Earth ruled by technological geniuses who live on human blood. They join the primitive resistance fighters who dwell outside the domed cities. Part of the short-lived Atlas science fiction line from former Marvel publisher Martin Goodman.

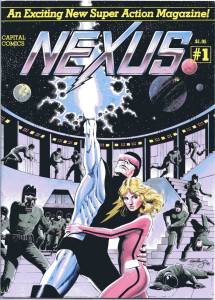

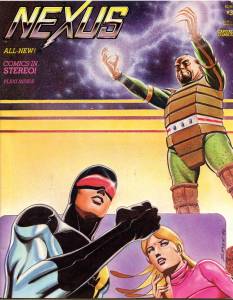

Nexus V1 – Capital Comics (1981)

Nexus is a comic book series created by writer Mike Baron and penciler Steve Rude in 1981. The series is a combination of the superhero and science fiction genres, set 500 years in the future.

The series debuted as a three-issue black-and-white limited series (the third of which featured a 33 RPM flexi disc with music and dialogue from the issue), followed by an eighty-issue ongoing full-color series. The black-and-white issues and the first six color issues were published by Capital Comics; after Capital’s demise, First Comics took over publication.

On the creation of the series: Baron noted that they had originally pitched a series called Encyclopaedias to Capital Comics, but the company rejected this, saying they were looking for a superhero title. Over a drink at a restaurant, Baron outlined his ideas for Nexus to Rude.

Nexus was entirely Baron’s idea. He even came up with the lightning bolt for the costume. All that we needed then was a name… a few weeks passed. Baron calls, and, without preamble, just says “Nexus.” We finally had our name.”

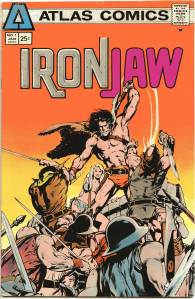

Ironjaw (1975)

Abandoned and left to die by order of his step-father the King, Ironjaw is discovered and raised by the bandit Tar-Lok. Later in life, his jaw is removed by a jealous group of thieves and replaced with a jaw made of iron.