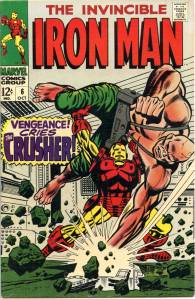

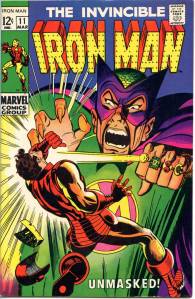

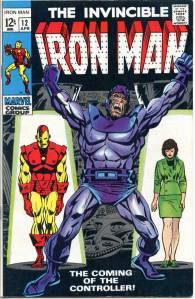

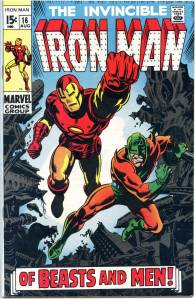

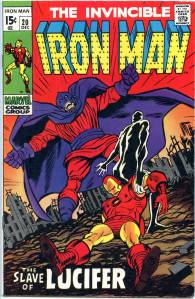

After issue #99 (March 1968), the Tales of Suspense series was renamed Captain America. An Iron Man story appeared in the one-shot comic Iron Man and Sub-Mariner (April 1968), before the “Golden Avenger”] made his solo debut with The Invincible Iron Man #1 (May 1968). The series’ indicia gives its copyright title Iron Man, while the trademarked cover logo of most issues is The Invincible Iron Man. Artist George Tuska began a decade long association with the character with Iron Man #5 (Sept. 1968). Writer Mike Friedrich and artist Jim Starlin‘s brief collaboration on the Iron Man series introduced Mentor, Starfox, and Thanos in issue #55 (Feb. 1973). Friedrich scripted a metafictional story in which Iron Man visited the San Diego Comic Convention and met several Marvel Comics writers and artists. He then wrote the multi-issue “War of the Super-Villains” storyline which ran through 1975.

Category: Marvel Silver Age

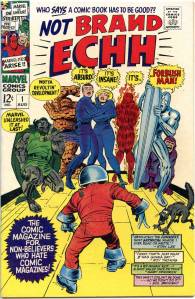

Not Brand Echh (1967)

Not Brand Echh is a satiric comic book series published by Marvel Comics that parodied its own superhero stories as well as those of other comics publishers. Running for 13 issues (cover-dated Aug. 1967 to May 1969), it included among its contributors such notable writers and artists as Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Gene Colan, Bill Everett, John and Marie Severin, and Roy Thomas. With issue #9, it became a 68-page, 25¢ “giant”, relative to the typical 12¢ comics of the times. In 2017, a 14th issue was released.

Its mascot, Forbush Man, introduced in the first issue, was a superhero wannabe with no superpowers and a costume of red long johns emblazoned with the letter “F” and a cooking pot, with eye-holes, covering his never-revealed head. His secret identity was eventually revealed in issue #5 (Dec. 1967) as Irving Forbush, Marvel’s fictitious office gofer.

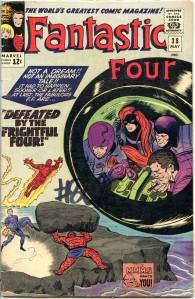

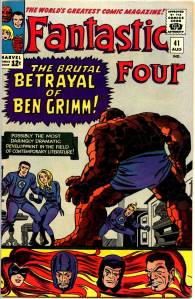

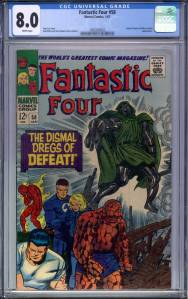

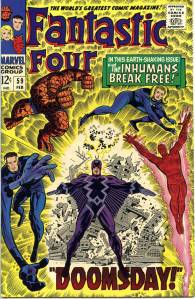

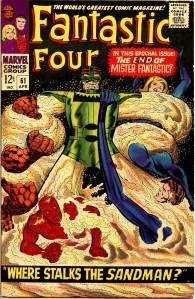

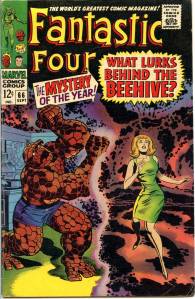

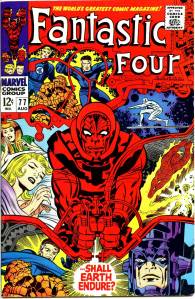

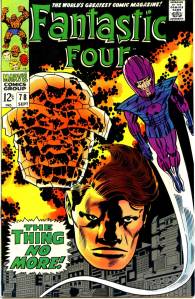

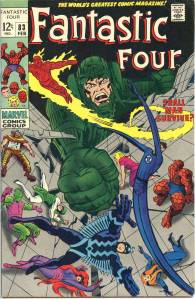

Fantastic Four (Silver Age)

The Fantastic Four debuted in The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961), which helped to usher in a new level of realism in the medium. The Fantastic Four was the first superhero team created by writer-editor Stan Lee and artist/co-plotter Jack Kirby, who developed a collaborative approach to creating comics with this title that they would use from then on. As the first superhero team title produced by Marvel Comics, it formed a cornerstone of the company’s 1960s rise from a small division of a publishing company to a pop culture conglomerate.

Strange Tales (Silver Age)

Strange Tales switched to superheroes during the Silver Age of Comic Books, retaining the sci-fi, suspense and monsters as backup features for a time. Strange Tales‘ first superhero, in 12- to 14-page stories, was the Fantastic Four‘s Human Torch, Johnny Storm, beginning in #101 (Oct. 1962). Here, Johnny still lived with his elder sister, Susan Storm, in fictional Glenview, Long Island, New York, where he continued to attend high school and, with youthful naivete, attempted to maintain his “secret identity” (later retconned to reveal that his friends and neighbors knew of his dual identity from Fantastic Four news reports, but simply played along).

The title became a “split book” with the introduction of sorcerer Doctor Strange, by Lee and artist Steve Ditko. This 9- to 10-page feature debuted in #110 (July 1963), and after an additional story and then skipping two issues returned permanently with #114. Ditko’s surrealistic mystical landscapes and increasingly head-trippy visuals helped make the feature a favorite of college students, according to Lee himself. Eventually, as co-plotter and later sole plotter, in the “Marvel Method“, Ditko would take Strange into ever-more-abstract realms, which yet remained well-grounded thanks to Lee’s reliably humanistic, adventure/soap opera dialog. Adversaries for the new hero included Baron Mordo introduced in issue #111 (Aug. 1963) and Dormammu in issue #126 (Nov. 1964). Clea, who would become a longtime love interest for Doctor Strange, was also introduced in issue #126.

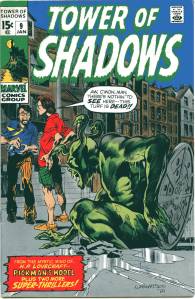

Towerl of Shadows (1969)

Designed to compete with DC Comics‘ successful launches of House of Mystery and House of Secrets,[2] Tower of Shadows, like its companion comic Chamber of Darkness, sold poorly despite the roster of artists featured. After its first few issues, the title, published bimonthly, began including reprints of “pre-superhero Marvel” monster stories and other SF/fantasy tales from Marvel’s 1950s and early 1960s predecessor, Atlas Comics. After the ninth issue, the title changed to Creatures on the Loose, and the comic became a mix of reprints and occasional sword and sorcery/SF series.

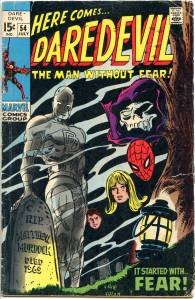

Daredevil (1964)

Daredevil debuted in Marvel Comics‘ Daredevil #1 (cover date April 1964), created by writer-editor Stan Lee and artist Bill Everett, with character design input from Jack Kirby, who devised Daredevil’s billy club. When Everett turned in his first-issue pencils extremely late, Marvel production manager Sol Brodsky and Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko inked a large variety of different backgrounds, a “lot of backgrounds and secondary figures on the fly and cobbled the cover and the splash page together from Kirby’s original concept drawing”.

Writer and comics historian Mark Evanier has concluded (but cannot confirm) that Kirby designed the basic image of Daredevil’s costume, though Everett modified it. The character’s original costume design was a combination of black, yellow, and red, reminiscent of acrobat tights. Wally Wood, known for his 1950s EC Comics stories, penciled and inked issues #5–10, introducing Daredevil’s modern red costume in issue #7.

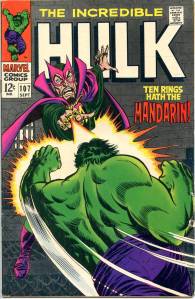

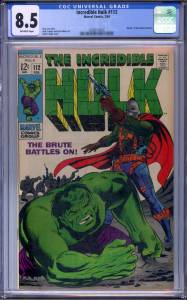

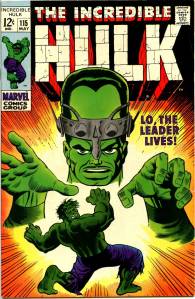

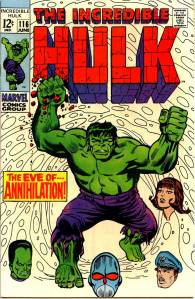

The Incredible Hulk V1 (1968)

The Hulk first appeared in The Incredible Hulk #1 (cover dated May 1962), written by writer-editor Stan Lee, penciled and co-plotted by Jack Kirby, and inked by Paul Reinman. Lee cites influence from Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in the Hulk’s creation. The Hulk’s original series was canceled with issue #6 (March 1963).

In the debut, Lee chose gray for the Hulk because he wanted a color that did not suggest any particular ethnic group. Colorist Stan Goldberg, however, had problems with the gray coloring, resulting in different shades of grey, and even green, in the issue. After seeing the first published issue, Lee chose to change the skin color to green. Green was used in retellings of the origin, with even reprints of the original story being recolored for the next two decades, until The Incredible Hulk vol. 2, #302 (December 1984) reintroduced the gray Hulk in flashbacks set close to the origin story. Since then, reprints of the first issue have displayed the original gray coloring, with the fictional canon specifying that the Hulk’s skin had initially been grey. An exception is the early trade paperback, Origins of Marvel Comics, from 1974, which explains the difficulties in keeping the gray color consistent in a Stan Lee written prologue, and reprints the origin story keeping the gray coloration.

Lee gave the Hulk’s alter ego the alliterative name Bruce Banner because he found he had less difficulty remembering alliterative names. Despite this, in later stories he misremembered the character’s name and referred to him as “Bob Banner”, an error which readers quickly picked up on. The discrepancy was resolved by giving the character the official full name of Robert Bruce Banner.

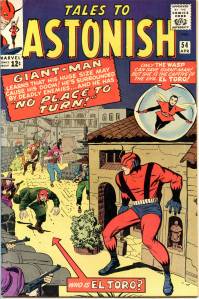

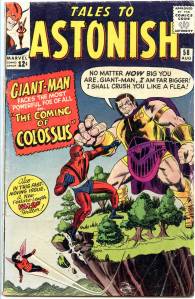

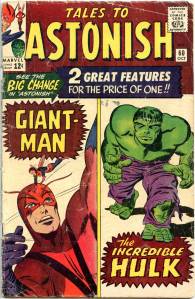

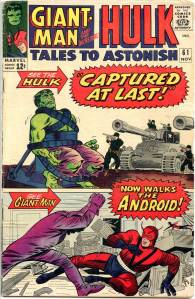

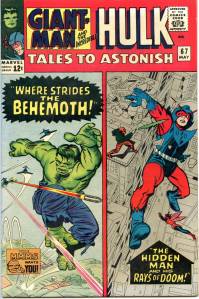

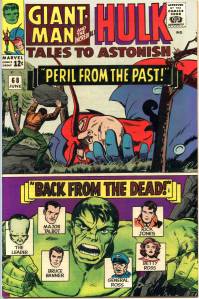

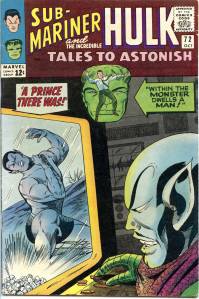

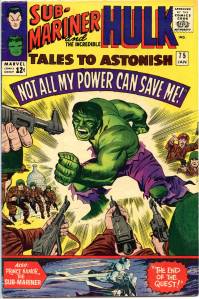

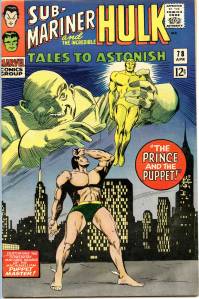

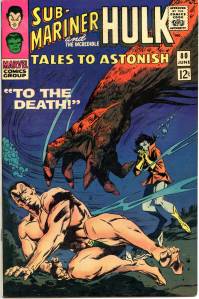

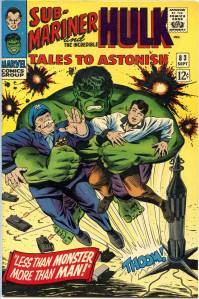

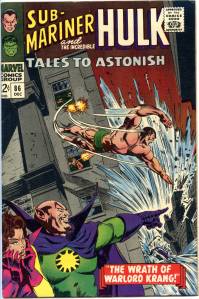

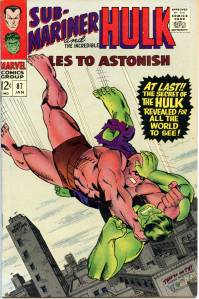

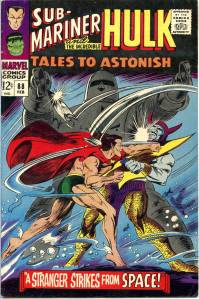

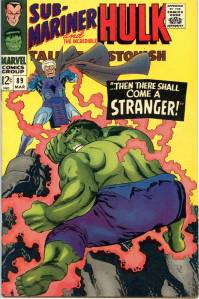

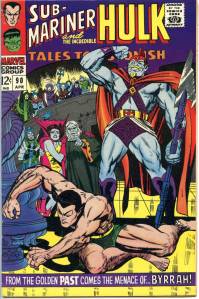

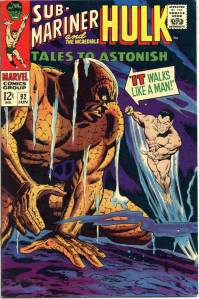

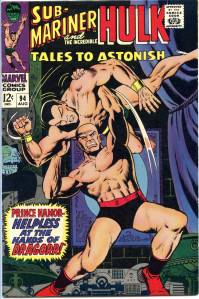

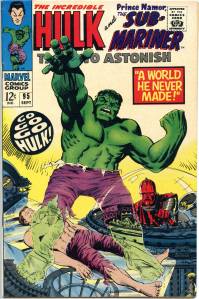

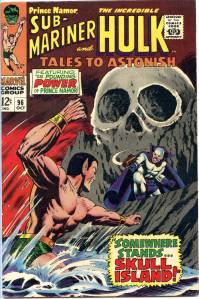

Tales to Astonish (Silver Age)

Tales to Astonish was published from January 1959 to March 1968 . It began as a science-finction anthology that served as a showcase for such artists as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. It became The Incredible Hulk with issue #102 (April 1968). Its sister title was Tales of Suspense.

Following his one-shot anthological story in #27 (Jan. 1962), scientist Henry Pym returned donning a cybernetic helmet and red costume, and using size-changing technology to debut as the insect-sized hero Ant-Man in #35 (Sept. 1962). The series was plotted by Lee and scripted by Lieber, with penciling first by Kirby and later by Heck and others. The Wasp was introduced as Ant-Man’s costar in issue #44 (June 1963). Ant-Man and Pym’s subsequent iteration, Giant-Man, introduced in #49 (Nov. 1963), starred in 10- to 13-page and later 18-page adventures,

The Hulk, whose original series The Incredible Hulk had been canceled after a six-issue run in 1962-63, returned to star in his own feature when Tales to Astonish became a split book at issue #60 (Oct. 1964),]after having guest-starred as Giant-Man’s antagonist in a full-length story the previous issue. The Hulk had proven a popular guest-star in three issues of Fantastic Four and an issue of The Amazing Spider-Man. His new stories here were initially scripted by Lee and illustrated by the seldom-seen team of penciler Steve Ditko and inker George Roussos. This early part of the Hulk’s run introduced the Leader, who would become the Hulk’s nemesis, and this run additionally made the Hulk’s identity known, initially only to the military and then later publicly.

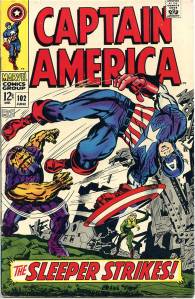

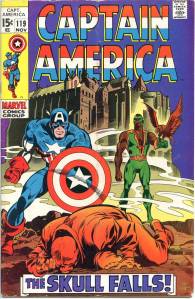

Captain America (1960’s)

Tales of Suspense became Captain America with #100 (April 1968) This series — considered Captain America volume one by comics researchers and historians, following the 1940s Captain America Comics and its 1950s numbering continuation of Tales of Suspense — ended with #454 (Aug. 1996).